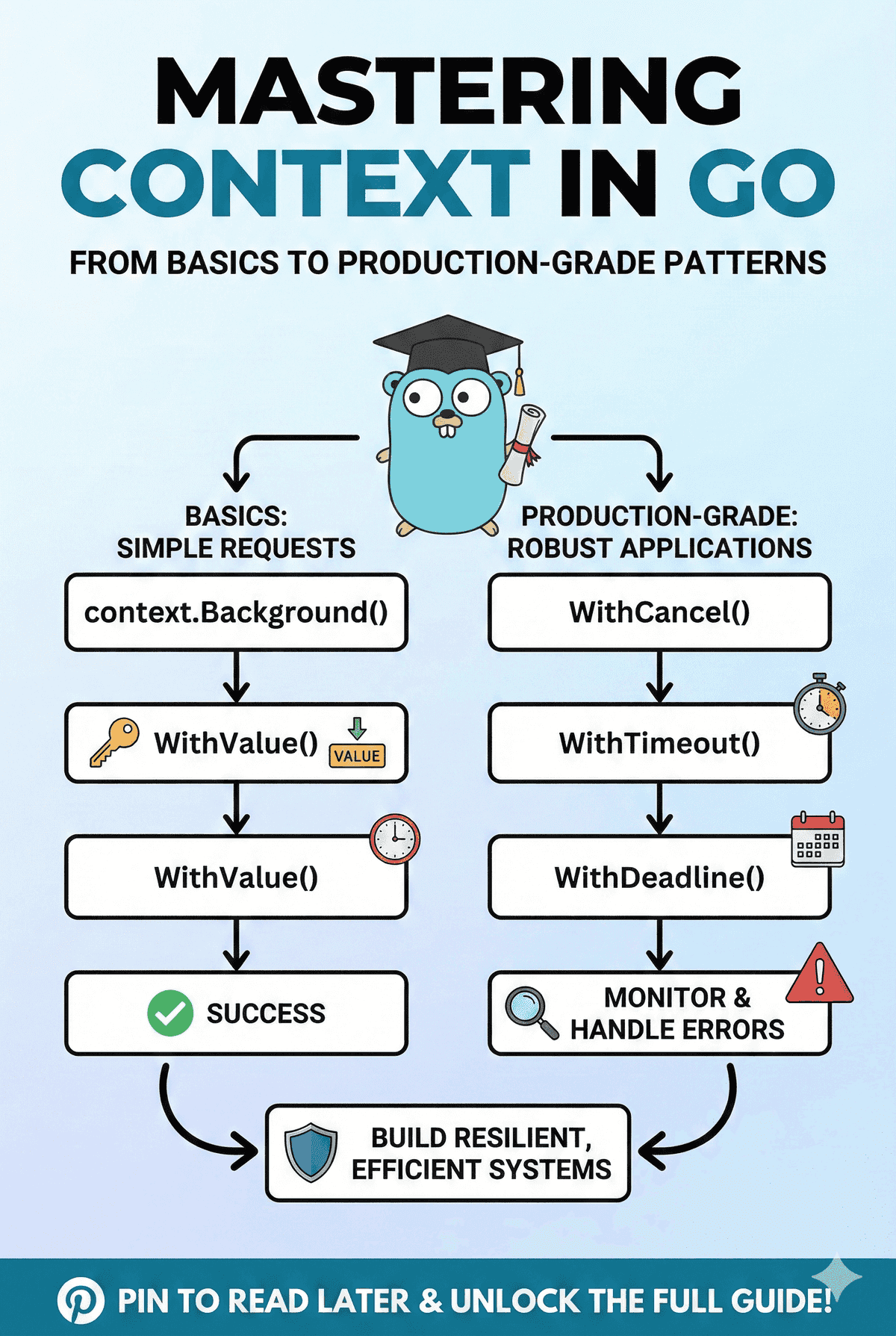

Mastering Context in Go: From Basics to Production-Grade Patterns

December 31, 2025

•11 min read

Mastering Context in Go: From Basics to Production-Grade Patterns

If you've worked with Go for more than a week, you've seen context.Context everywhere: HTTP handlers, database calls, gRPC methods, and pretty much any I/O operation. But why does context exist, and how do you use it effectively in production microservices?

In this post, I'll walk you through:

- What problem context solves (and what it doesn't)

- The three core use cases: cancellation, timeouts, and value propagation

- A practical implementation with real code and tests

- Production patterns I've used in Go microservices

By the end, you'll understand not just how to pass context around, but when and why it matters.

The problem: coordinating lifecycle across goroutines

Imagine a typical web request in a microservice:

- HTTP handler receives request

- Spawns goroutines to query multiple services in parallel

- Aggregates results and returns response

What happens if:

- The client disconnects before the response is ready?

- The request times out before all goroutines finish?

- You need to pass request-scoped data (trace ID, user ID) across function boundaries?

Without context, you'd need to:

- Manually pass cancellation signals through channels

- Track timeouts with separate timers

- Thread metadata through every function signature

Context solves all three problems with a single, idiomatic interface.

What is context.Context?

context.Context is an interface that carries:

- Cancellation signals: When work should stop

- Deadlines: When work must stop

- Request-scoped values: Metadata that travels with the request

type Context interface {

Deadline() (deadline time.Time, ok bool)

Done() <-chan struct{}

Err() error

Value(key interface{}) interface{}

}Key insights:

- Immutable: Once created, a context never changes (you derive new contexts)

- Safe for concurrent use: Multiple goroutines can read from the same context

- Forms a tree: Child contexts inherit from parents but can have tighter constraints

Use Case 1: Cancellation (stop work when it's no longer needed)

When a client disconnects or upstream work is cancelled, you want downstream work to stop immediately—not waste CPU and keep connections open.

Example: Simulate cancellable work

func SimulateWork(ctx context.Context, workDuration time.Duration, description string) error {

timer := time.NewTimer(workDuration)

defer timer.Stop()

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

// Context was cancelled—stop immediately

return ctx.Err()

case <-timer.C:

// Work completed successfully

return nil

}

}Why this matters in production

In a real HTTP handler:

func SearchHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := r.Context() // Inherits cancellation from HTTP server

// If the client closes the connection, ctx.Done() fires automatically

results, err := performExpensiveSearch(ctx, query)

if err != nil {

// Could be context.Canceled if client disconnected

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(results)

}Without context, the expensive search would run to completion even if the client already left.

Use Case 2: Timeouts (fail fast instead of hanging forever)

Database calls, HTTP requests, and RPCs can hang. Timeouts prevent one slow dependency from blocking your entire service.

Example: Context with timeout

func FetchWithTimeout(url string, timeout time.Duration) (string, error) {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), timeout)

defer cancel()

req, err := http.NewRequestWithContext(ctx, "GET", url, nil)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

resp, err := http.DefaultClient.Do(req)

if err != nil {

// Could be context.DeadlineExceeded

return "", err

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

body, _ := io.ReadAll(resp.Body)

return string(body), nil

}Why defer cancel() matters

Even if the request completes successfully, you must call cancel() to release resources (timers, goroutines) associated with the context.

Best practice: Always defer cancel() immediately after creating a cancellable or timeout context.

Use Case 3: Value propagation (request-scoped metadata)

Sometimes you need to pass data across function boundaries without polluting every function signature: trace IDs, user IDs, request IDs, authentication tokens.

Example: Adding and retrieving values

func AddValue(parent context.Context, key, value interface{}) context.Context {

return context.WithValue(parent, key, value)

}

func GetValue(ctx context.Context, key interface{}) (interface{}, bool) {

val := ctx.Value(key)

if val == nil {

return nil, false

}

return val, true

}In production: structured logging with trace IDs

type contextKey string

const (

traceIDKey contextKey = "traceID"

requestIDKey contextKey = "requestID"

)

func WithTraceID(ctx context.Context, traceID string) context.Context {

return context.WithValue(ctx, traceIDKey, traceID)

}

func GetTraceID(ctx context.Context) (string, bool) {

val := ctx.Value(traceIDKey)

if val == nil {

return "", false

}

traceID, ok := val.(string)

return traceID, ok

}Warning: Don't abuse context.WithValue for things that should be function parameters. Use it for request-scoped data that crosses abstraction boundaries (like observability metadata).

Practical implementation: ContextManager

Let me show you a simple ContextManager interface that wraps the common patterns. This is useful when building reusable libraries or when you want to standardize context handling across your codebase.

type ContextManager interface {

// Create a cancellable context from a parent context

CreateCancellableContext(parent context.Context) (context.Context, context.CancelFunc)

// Create a context with timeout

CreateTimeoutContext(parent context.Context, timeout time.Duration) (context.Context, context.CancelFunc)

// Add a value to context

AddValue(parent context.Context, key, value interface{}) context.Context

// Get a value from context

GetValue(ctx context.Context, key interface{}) (interface{}, bool)

// Execute a task with context cancellation support

ExecuteWithContext(ctx context.Context, task func() error) error

// Wait for context cancellation or completion

WaitForCompletion(ctx context.Context, duration time.Duration) error

}Implementation

type simpleContextManager struct{}

func NewContextManager() ContextManager {

return &simpleContextManager{}

}

func (cm *simpleContextManager) CreateCancellableContext(parent context.Context) (context.Context, context.CancelFunc) {

return context.WithCancel(parent)

}

func (cm *simpleContextManager) CreateTimeoutContext(parent context.Context, timeout time.Duration) (context.Context, context.CancelFunc) {

return context.WithTimeout(parent, timeout)

}

func (cm *simpleContextManager) AddValue(parent context.Context, key, value interface{}) context.Context {

return context.WithValue(parent, key, value)

}

func (cm *simpleContextManager) GetValue(ctx context.Context, key interface{}) (interface{}, bool) {

val := ctx.Value(key)

if val == nil {

return nil, false

}

return val, true

}The tricky one: ExecuteWithContext

This is where context cancellation gets interesting. You want to run a task in a goroutine, but stop it if the context is cancelled:

func (cm *simpleContextManager) ExecuteWithContext(ctx context.Context, task func() error) error {

ctx, cancel := cm.CreateCancellableContext(ctx)

defer cancel()

done := make(chan error, 1)

// Run task in goroutine

go func() {

done <- task()

}()

// Race: who finishes first?

select {

case err := <-done:

return err // Task completed first

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err() // Context cancelled/timeout first

}

}Key insight: The select statement races the task completion against context cancellation. Whichever happens first determines the outcome.

WaitForCompletion: A context-aware sleep

func (cm *simpleContextManager) WaitForCompletion(ctx context.Context, duration time.Duration) error {

timer := time.NewTimer(duration)

defer timer.Stop()

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err() // Context cancelled

case <-timer.C:

return nil // Duration elapsed successfully

}

}This is useful when you need to wait for a fixed duration, but want to respect cancellation (e.g., graceful shutdown, backoff delays).

Real-world example: Processing items with cancellation

This pattern shows up constantly in batch processing, ETL pipelines, and background workers:

func ProcessItems(ctx context.Context, items []string) ([]string, error) {

const perItemWork = 40 * time.Millisecond

results := make([]string, 0, len(items))

for _, item := range items {

// Check cancellation before processing each item

if err := ctx.Err(); err != nil {

return results, err // Return partial results

}

timer := time.NewTimer(perItemWork)

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

timer.Stop()

return results, ctx.Err()

case <-timer.C:

// Process the item

results = append(results, "processed_"+item)

}

}

return results, nil

}Production note: This pattern ensures that if a batch job is cancelled (e.g., during deployment or shutdown), you get partial results and a clean exit instead of orphaned goroutines.

Testing context behavior

Context behavior is subtle, so testing is critical. Here are the high-value tests:

Test 1: Cancellation propagates correctly

func TestExecuteWithContext_Cancellation(t *testing.T) {

cm := NewContextManager()

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

// Long running task

task := func() error {

time.Sleep(200 * time.Millisecond)

return nil

}

// Cancel after a short delay

go func() {

time.Sleep(50 * time.Millisecond)

cancel()

}()

err := cm.ExecuteWithContext(ctx, task)

if err != context.Canceled {

t.Errorf("Expected context.Canceled, got %v", err)

}

}Test 2: Timeout fires correctly

func TestCreateTimeoutContext(t *testing.T) {

cm := NewContextManager()

timeout := 50 * time.Millisecond

ctx, cancel := cm.CreateTimeoutContext(context.Background(), timeout)

defer cancel()

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

if ctx.Err() != context.DeadlineExceeded {

t.Errorf("Expected context.DeadlineExceeded, got %v", ctx.Err())

}

case <-time.After(100 * time.Millisecond):

t.Fatal("Context should timeout after specified duration")

}

}Test 3: Values survive context derivation

func TestAddAndGetValue(t *testing.T) {

cm := NewContextManager()

ctx := context.Background()

ctx = cm.AddValue(ctx, "user", "alice")

ctx = cm.AddValue(ctx, "requestID", "12345")

value, exists := cm.GetValue(ctx, "user")

if !exists || value != "alice" {

t.Fatal("Expected user value to exist and equal 'alice'")

}

value, exists = cm.GetValue(ctx, "nonexistent")

if exists {

t.Error("Expected nonexistent value to not exist")

}

}Production patterns I actually use

After shipping context-heavy Go services to production, here are the patterns that stuck:

1. Always derive from request context in HTTP handlers

func MyHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := r.Context() // Already has cancellation + deadlines from server

// Use ctx for all downstream calls

}2. Add timeouts at service boundaries

func CallExternalAPI(ctx context.Context, url string) ([]byte, error) {

// Enforce a tight timeout for external calls

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 2*time.Second)

defer cancel()

req, _ := http.NewRequestWithContext(ctx, "GET", url, nil)

resp, err := http.DefaultClient.Do(req)

// ...

}3. Use typed keys for context values

type contextKey string

const (

userIDKey contextKey = "userID"

requestIDKey contextKey = "requestID"

)

// Prevents collisions with other packages using string keys4. Propagate cancellation to all goroutines

func FanOut(ctx context.Context, tasks []func() error) error {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(ctx)

defer cancel()

errCh := make(chan error, len(tasks))

for _, task := range tasks {

task := task // Capture loop variable

go func() {

errCh <- task()

}()

}

// Wait for first error or all completions

for range tasks {

if err := <-errCh; err != nil {

cancel() // Cancel all other goroutines

return err

}

}

return nil

}5. Graceful shutdown with context

func (s *Server) Shutdown(timeout time.Duration) error {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), timeout)

defer cancel()

// Shut down HTTP server with context

return s.httpServer.Shutdown(ctx)

}Common pitfalls (and how to avoid them)

❌ Pitfall 1: Not checking context errors

// BAD: Ignoring context cancellation

func Process(ctx context.Context) {

for {

doWork()

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

}

// GOOD: Checking ctx.Done()

func Process(ctx context.Context) {

ticker := time.NewTicker(1 * time.Second)

defer ticker.Stop()

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return // Clean exit

case <-ticker.C:

doWork()

}

}

}❌ Pitfall 2: Using context for optional parameters

// BAD: Using context for business logic

func CreateUser(ctx context.Context) error {

email := ctx.Value("email").(string) // Fragile, not obvious

// ...

}

// GOOD: Use function parameters

func CreateUser(ctx context.Context, email string) error {

// ...

}❌ Pitfall 3: Not calling cancel()

// BAD: Leaking resources

func BadTimeout() {

ctx, _ := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 5*time.Second)

// Forgot to call cancel() - timer leaks

doWork(ctx)

}

// GOOD: Always defer cancel()

func GoodTimeout() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 5*time.Second)

defer cancel() // Releases timer even if doWork returns early

doWork(ctx)

}❌ Pitfall 4: Passing nil context

// BAD: Causes panics

func Process(ctx context.Context) {

// If ctx is nil, this panics

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

}

}

// GOOD: Use context.Background() or context.TODO()

func Process() {

ctx := context.Background()

// Or context.TODO() if you plan to replace it later

}When NOT to use context

Context is not a silver bullet. Don't use it for:

- Configuration: Use config structs or dependency injection

- Business logic state: Use function parameters or struct fields

- Database transactions: Use

*sql.Txexplicitly - Authentication/authorization objects: Pass them explicitly or use middleware

Performance considerations

Context operations are designed to be fast, but not free:

- Value lookups are O(n): Context values form a linked list, so deep chains are slow. Keep context chains shallow.

- Cancellation is O(n): Broadcasting to (n) child contexts takes (O(n)) time.

- Every

WithValueallocates: If you're in a super hot path (millions of QPS), consider alternatives.

For 99% of Go services, context overhead is negligible. Profile before optimizing.

Conclusion: Context is about coordination, not configuration

The Go context package is elegant because it solves three hard problems (cancellation, timeouts, value propagation) with one simple interface.

The key mental model:

Context flows downstream with your request, carrying deadlines and metadata, and fires cancellation signals when work should stop.

If you internalize that model, you'll write Go code that's:

- Resilient: Fails fast instead of hanging

- Efficient: Cancels work when it's no longer needed

- Observable: Propagates trace IDs and request metadata

- Idiomatic: Uses the patterns every Go developer expects

This blog was inspired by Go Interview Challenge 30, which tasks you to dig into real-world Go context management across microservices. The patterns, examples, and code in this post reflect practical lessons learned from tackling those scenarios. If you're preparing for Go interviews or want to strengthen your understanding of context in production, the original challenge is a great way to get hands-on.

Happy coding! 🚀