Benchmarking in Go: Measure Performance with Real Examples (Sorting + strings.Builder)

December 28, 2025

��•7 min read

Benchmarking in Go: Measure Performance with Real Examples (Sorting + strings.Builder)

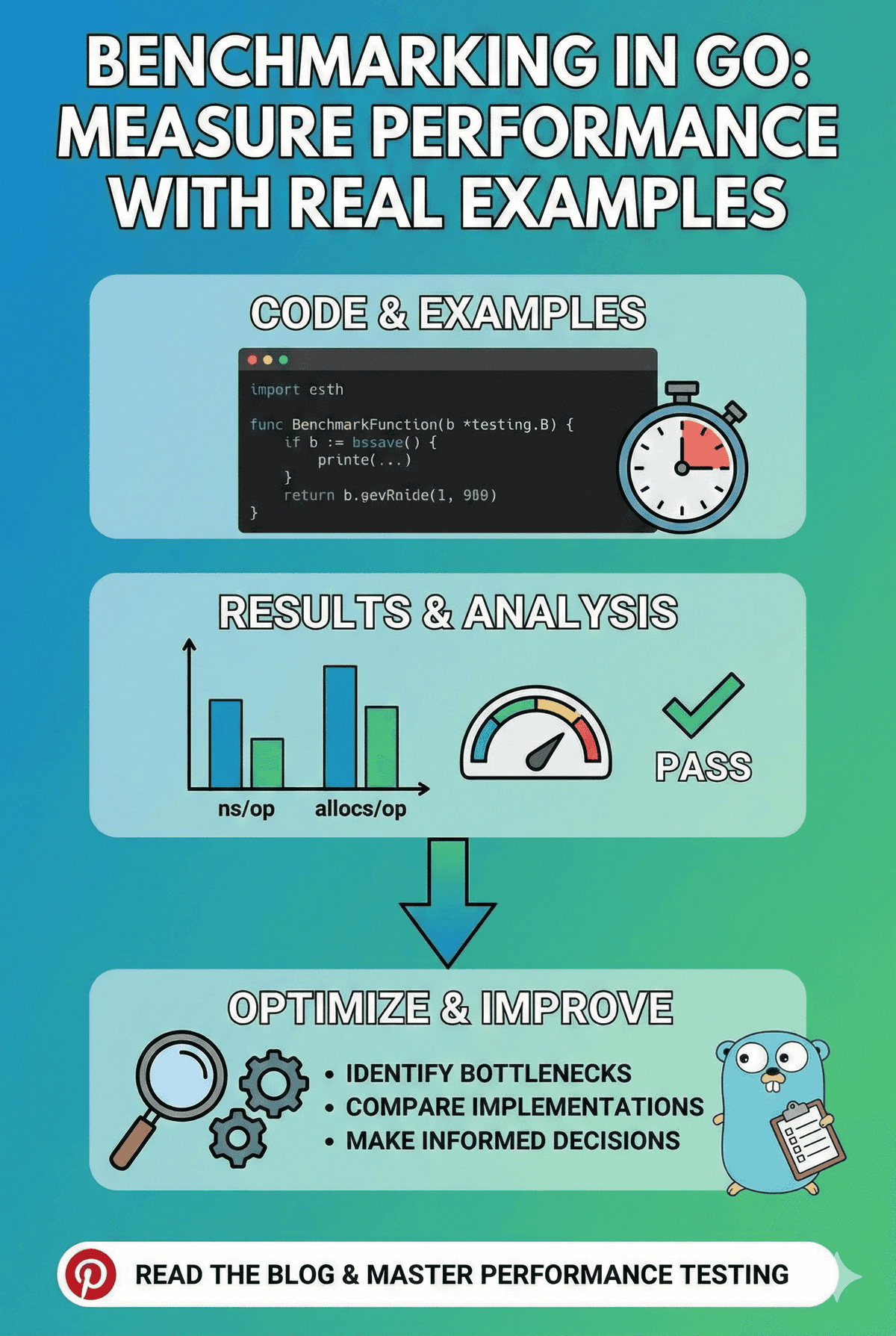

Benchmarking in Go isn’t a “nice to have” — it’s how you avoid guessing. The fastest way to waste time in performance work is to optimize blindly, then ship code that “feels faster” but isn’t.

In this post, I’ll explain what Go benchmarks are, how to run them, how to read the output, and I’ll use two concrete examples:

- Sorting: bubble sort vs Go’s optimized sort (

slices.Sort) - Strings:

+=concatenation vsstrings.Builder

What is benchmarking in Go?

A benchmark measures how long a piece of code takes to run (and optionally how much memory it allocates). In Go, benchmarks live next to tests in _test.go files and use the testing package.

A benchmark function:

- Starts with

Benchmark... - Accepts a

*testing.B - Runs the target operation

b.Ntimes (Go automatically choosesb.Nto stabilize the timing)

Example skeleton:

func BenchmarkMyFunction(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

MyFunction()

}

}Example 1: Sorting (bubble sort vs slices.Sort)

The “slow” version (bubble sort)

This version is intentionally inefficient: (O(n^2)).

// SlowSort sorts a slice of integers using a very inefficient algorithm (bubble sort)

func SlowSort(data []int) []int {

// Make a copy to avoid modifying the original

result := make([]int, len(data))

copy(result, data)

// Bubble sort implementation

for i := 0; i < len(result); i++ {

for j := 0; j < len(result)-1; j++ {

if result[j] > result[j+1] {

result[j], result[j+1] = result[j+1], result[j]

}

}

}

return result

}The optimized version (standard library sort)

Same output, better algorithmic complexity in practice ((O(n \log n)) average).

import "slices"

// OptimizedSort is an optimized version of SlowSort

func OptimizedSort(data []int) []int {

sorted := make([]int, len(data))

copy(sorted, data)

slices.Sort(sorted)

return sorted

}Correctness test (optimized must match slow)

Before caring about speed, we ensure both functions return identical results:

func TestOptimizedSort(t *testing.T) {

testCases := []struct {

name string

input []int

}{

{"Empty", []int{}},

{"One Element", []int{42}},

{"Already Sorted", []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}},

{"Reverse Sorted", []int{5, 4, 3, 2, 1}},

{"Random Order", []int{3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9, 2, 6}},

{"Random Large", generateRandomSlice(100)},

}

for _, tc := range testCases {

t.Run(tc.name, func(t *testing.T) {

slowResult := SlowSort(tc.input)

optimizedResult := OptimizedSort(tc.input)

if !slicesEqual(slowResult, optimizedResult) {

t.Errorf("OptimizedSort gave different results than SlowSort. Got %v, expected %v", optimizedResult, slowResult)

}

})

}

}Benchmark code (the important part)

Benchmarks are just code that runs your function b.N times:

func BenchmarkSlowSort(b *testing.B) {

sizes := []int{10, 100, 1000}

for _, size := range sizes {

data := generateRandomSlice(size)

b.Run(fmt.Sprint(size), func(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

SlowSort(data)

}

})

}

}

func BenchmarkOptimizedSort(b *testing.B) {

sizes := []int{10, 100, 1000}

for _, size := range sizes {

data := generateRandomSlice(size)

b.Run(fmt.Sprint(size), func(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

OptimizedSort(data)

}

})

}

}Real results (my run)

Environment:

- OS/Arch:

darwin/arm64 - Go:

go1.25.1 - Command:

go test -run '^$' -bench '.' -benchmem -count=3

For 1000 elements:

- SlowSort: ~580–588 µs/op

- OptimizedSort: ~9.7 µs/op

- Speedup: ~60× faster

Representative lines:

BenchmarkSlowSort/1000-8 587459 ns/op 8192 B/op 1 allocs/op

BenchmarkOptimizedSort/1000-8 9740 ns/op 8192 B/op 1 allocs/opExample 2: Building strings (+= vs strings.Builder)

The “slow” version (repeated +=)

This looks innocent, but it repeatedly allocates and copies as the string grows.

// InefficientStringBuilder builds a string by repeatedly concatenating

func InefficientStringBuilder(parts []string, repeatCount int) string {

result := ""

for i := 0; i < repeatCount; i++ {

for _, part := range parts {

result += part

}

}

return result

}The optimized version (strings.Builder)

strings.Builder is the idiomatic way to build strings efficiently.

import "strings"

// OptimizedStringBuilder is an optimized version of InefficientStringBuilder

func OptimizedStringBuilder(parts []string, repeatCount int) string {

var builder strings.Builder

for i := 0; i < repeatCount; i++ {

for _, part := range parts {

builder.WriteString(part)

}

}

return builder.String()

}Correctness test (optimized must match slow)

func TestOptimizedStringBuilder(t *testing.T) {

testCases := []struct {

name string

parts []string

repeatCount int

}{

{"Empty", []string{}, 10},

{"Single Part", []string{"Hello"}, 5},

{"Multiple Parts", []string{"Hello", " ", "World", "!"}, 3},

{"Large Build", []string{"This", " ", "is", " ", "a", " ", "test"}, 100},

}

for _, tc := range testCases {

t.Run(tc.name, func(t *testing.T) {

inefficientResult := InefficientStringBuilder(tc.parts, tc.repeatCount)

optimizedResult := OptimizedStringBuilder(tc.parts, tc.repeatCount)

if optimizedResult != inefficientResult {

t.Errorf("OptimizedStringBuilder gave different results than InefficientStringBuilder. Got %q, expected %q", optimizedResult, inefficientResult)

}

})

}

}Real results (my run)

The “Large” case is where the difference becomes obvious:

- Inefficient: ~4.28–4.38 ms/op, ~70 MB/op, ~7003 allocs/op

- Optimized: ~26.7–27.5 µs/op, ~84 KB/op, 18 allocs/op

- Speedup: ~160× faster

- Alloc reduction: ~7003 → 18 allocs/op

Representative lines:

BenchmarkInefficientStringBuilder/Large-8 4277351 ns/op 70153813 B/op 7004 allocs/op

BenchmarkOptimizedStringBuilder/Large-8 27495 ns/op 84729 B/op 18 allocs/opHow to run benchmarks (exact commands)

You can run benchmarks locally without any special tooling — it’s just go test with -bench.

If you want to benchmark a single file submission (like in this challenge), copy your code + the _test.go file into a temp folder:

cd /Users/younesbouchbouk/dev/go-interview-practice/challenge-16

tmp="$(mktemp -d)"

cp "submissions/YounesBouchbouk/solution-template.go" "solution-template_test.go" "$tmp/"

cd "$tmp"

go mod init challenge

# Run only benchmarks, skip tests

go test -run '^$' -bench '.' -benchmem

# More stable results

go test -run '^$' -bench '.' -benchmem -count=3Running one benchmark (or a subset)

# Sorting only

go test -run '^$' -bench 'OptimizedSort|SlowSort' -benchmem

# String building only

go test -run '^$' -bench 'OptimizedStringBuilder|InefficientStringBuilder' -benchmemHow to read Go benchmark results (ns/op, B/op, allocs/op)

You’ll typically see output like:

BenchmarkSomething-8 1000000 123 ns/op 16 B/op 1 allocs/opHere’s what matters:

ns/op: nanoseconds per operation (lower is better)B/op: bytes allocated per operation (lower is better)allocs/op: number of heap allocations per operation (lower is better)-8: the GOMAXPROCS value (how many logical CPUs the benchmark used)

Tip: Always run with

-benchmemwhen optimizing. It’s common to make code faster while accidentally allocating more, which can hurt real production latency under GC pressure.

The full raw output from my run is stored next to this post in benchmarks.txt.

Best practices (what I actually do in real Go services)

- Benchmark the real hot path: benchmark the function at the boundary where it matters (e.g., request handler, serialization step, DB mapping).

- Use

-benchmem: allocations are latency in disguise. - Run multiple times:

-count=3(or more) helps avoid noise. - Compare runs with

benchstat:

go test -run '^$' -bench '.' -benchmem -count=5 > old.txt

# change code

go test -run '^$' -bench '.' -benchmem -count=5 > new.txt

benchstat old.txt new.txt- Profile when you’re stuck: if the benchmark shows you’re slow but you don’t know why, use

pprof(CPU + heap profiles).

Conclusion

Go makes benchmarking ridiculously accessible. The workflow is simple:

- Write benchmarks for the code you care about

- Run

go test -bench ... -benchmem - Change one thing

- Measure again

That “measure → optimize → measure” loop is exactly how you get fast, reliable Go code without guessing.

This blog was inspired by Go Interview Challenge 16, which tasks you to dig into real-world Go benchmarking for sorting and string building. The practical lessons, examples, and code here draw directly from working through that challenge. If you're prepping for Go interviews, or just want to sharpen your performance intuition, you’ll find the original challenge a great hands-on exercise.

Happy benchmarking! 🚀